Groundbreaking achievements in science are often the culmination of smaller discoveries made by various scientists. The creation of the atomic bomb was not the result of one person’s work or a single project. Names like Robert Oppenheimer and the Manhattan Project are widely recognised, but behind their success were contributions from dozens of other scientists. Among them was Birmingham chemist Francis Aston. More on ibirmingham.

Best in Class

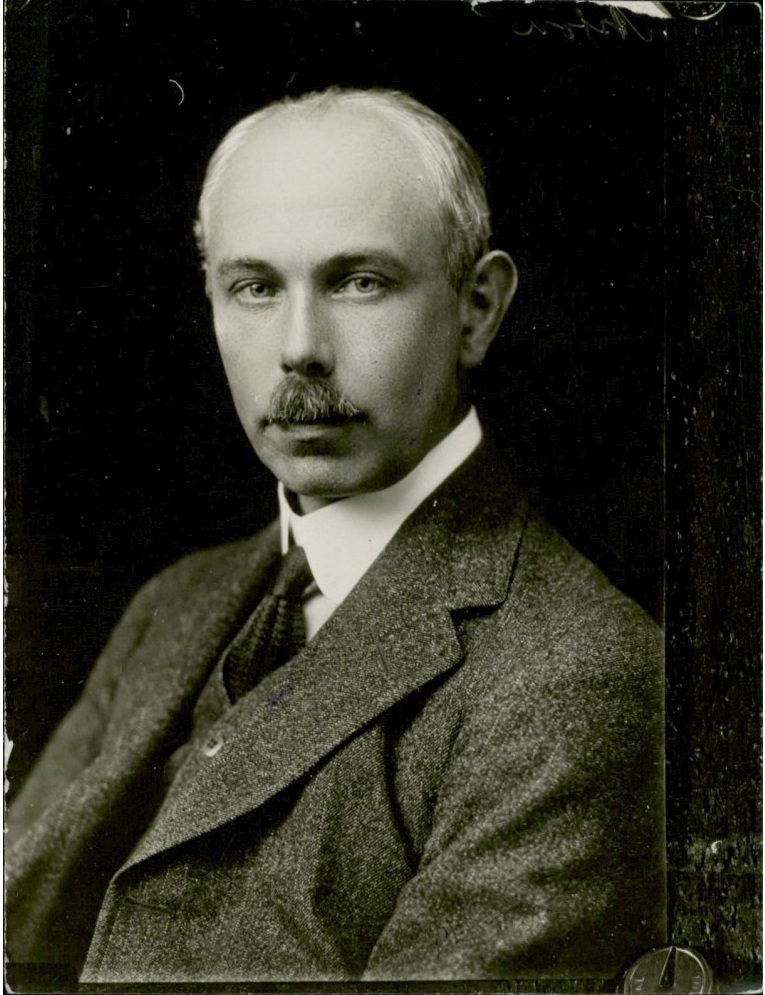

Francis Aston was born in Harborne in 1877, a time when Harborne was a suburb of Birmingham before it became part of the city. His father was an iron goods merchant, while his mother came from a family of successful Birmingham gunsmiths. From an early age, Aston showed great promise in science. He first studied at Harborne School and later at Malvern College, where he excelled as the top student in his class.

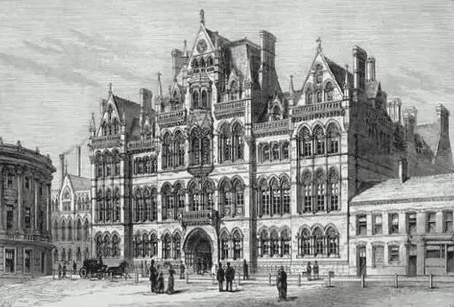

He pursued higher education at Mason College, a boarding school in Worcestershire that was part of the University of Birmingham.

At Mason College, Aston studied the exact sciences under renowned professors such as John Henry Poynting, Percy Frankland, and William Tilden. Chemistry particularly captivated the young scientist. In his father’s house, he set up a small laboratory where he conducted his first experiments. One of his early studies involved tartaric acid compounds. He also explored enzymatic chemistry while working at a Birmingham brewery. By 1900, he was officially employed at Butler & Co., where his findings proved useful to local brewers.

Return to Alma Mater

Despite financial difficulties during his studies, Aston remained devoted to science, taking on various part-time jobs. In his home laboratory, he built equipment to measure electrical discharges in vacuum tubes. His experiments proved successful, and in 1903, he returned to pursue postgraduate studies at the University of Birmingham. At the university, Aston focused on radioactivity and X-rays. Much of his research centred on the “Crookes dark space,” leading to his discovery of the “Aston dark space.” For this work, he earned a Bachelor of Applied Sciences degree, and in 1914, he completed his doctorate. Following this, he began lecturing.

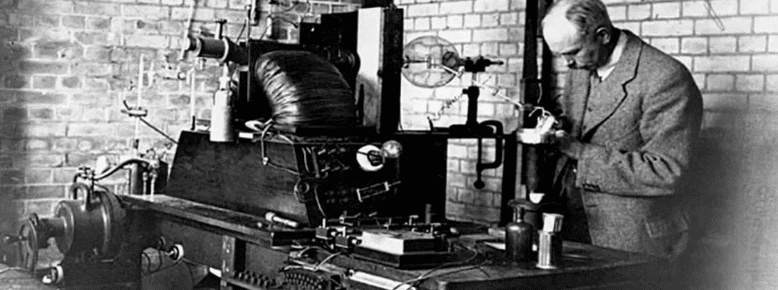

In Cambridge, Aston had the opportunity to collaborate with J. J. Thomson, the discoverer of the electron. Together, they investigated anode rays, which led to the development of the first mass spectrograph. Their work was the first to suggest the existence of isotopes. Aston concentrated on isotopes such as those of neon, chlorine, and mercury. However, when World War I broke out, Aston’s skills were required at the Royal Aircraft Factory in Farnborough, where he developed aviation coatings.

A Dangerous Discovery

After the war, Aston returned to Cambridge and resumed his research, identifying 212 natural isotopes of various elements. This work led to his formulation of the Whole Number Rule, which became fundamental to future studies in nuclear energy. In 1922, he was awarded the Nobel Prize in Chemistry. Aston’s contributions were highly valued in the physics community. He later developed more advanced versions of the mass spectrograph. Aston documented his research in numerous books, sharing not only scientific data but also his reflections on nuclear energy. He passed away in 1945, having lived to see the defining moment in global physics—the creation of the atomic bomb. Though in his later years, his earlier discoveries indirectly contributed to the Manhattan Project and the development of “Little Boy.”

A Million Passions

Francis Aston’s biography might give the impression that his life was solely devoted to science, but that wasn’t the case. He was an avid sports enthusiast, enjoying winter sports like skiing and ice skating, as well as mountaineering, which took him to Norway and Switzerland.

Aston was also passionate about cycling. As a young man, it was his primary mode of transportation. When motorised vehicles became available, he built an internal combustion engine and took an interest in motor racing. In 1903, he participated in the famous Gordon Bennett Cup in Ireland. Beyond risky sports, Aston enjoyed playing tennis, swimming, and golf, often involving his Cambridge colleagues in these activities.

Despite coming from a family tied to industry, Aston was instilled with a love of music from an early age. He was skilled at playing the piano, violin, and cello, and he regularly performed at social events and gatherings in Cambridge.

As a physicist, Aston understood the intricacies of the world, and travel became a source of inner peace for him. Following his father’s death, he embarked on a round-the-world trip, reaching destinations as far as Australia and New Zealand, which he visited just a few years before his death. His expedition to Sumatra in 1932 had a scientific purpose, as he participated in a study of solar eclipses. World War II and his passing prevented him from fulfilling his dream of visiting South Africa and Brazil. Francis Aston never married, as his packed schedule left no room for a wife or children.